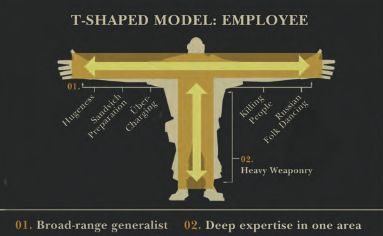

“T-shaped” people model misuse

In Handbook for new employees (PDF, 4 MB), Valve introduced on page 47 a concept of “T-shaped” people. What it means that people who want to work at Valve are expected to be both generalists—“highly skilled at a broad set of valuable things” and experts—“among the best in their field within a narrow discipline.”

This model was used by numerous other companies, but not in its original form. A popular application of the model is the expectation that a team member will be able to perform not only a specific subset of project tasks which correspond to his expertise, but also virtually any task related to the project. For instance, a developer with a strong background in Java and working on a web application should not limit himself to server-side programming, but is expected to handle a feature which also involves client-side (which could, for instance, involve TypeScript, React, HTML and CSS, as well as a decent knowledge of HTTP) and operations (which can also involve a bunch of technologies and protocols). Agile and DevOps encouraged this vision.

In this perspective, the original model appears overly simplistic. People are not just “T,” “I” and “‒.” Things are way more complex than that. Every skill has a relative value on a mastering scale.

While the person is rather a Java developer, he is knowledgeable when it comes to operations tasks with the technology stack used by the team; he knows damn well HTTP protocol; he has a good understanding of React—not as good as if he were a full client-side developer working with React since 2013, but good enough to perform well enough most of the tasks which involve React... I think you get the point. By measuring many of the skills and ordering them by the inverse of expertise level, one can build a curve:

Other persons may have different curves. In the case of A, the person has a broad range of skills, but no strong specialization—Jack of all trades, master of none. The chart B shows a person with interesting skills, but they are limited to a narrow domain: it usually means that the person will not be inclined to contribute to other domains. Those two dimensions—the specialized proficiency and the range of skills—is already represented in the “T-shaped” people model. What is missing, however, is the falloff, i.e. how fast the skills of a person decrease outside his domain of expertise.

The falloff is essential. If active involvement of a person is required in all facets of the project, he should have a decent understanding of every technology being used. If this is not the case, the team member will be a burden most of the time, either requiring constant help from other team members, or implementing things on his own without the basic understanding of what he's doing.

Important note: the chart of the skills of the person is project-dependent, since it strictly involves the skills directly useful for the project. In the previous example, if the person is proficient in C, his C skills are mostly irrelevant, and won't figure in the chart.

So we got those charts for several candidates. How does it helps us choosing the one we'll hire?

Most project will value candidates with a decent expertise level for the primary skill, a coverage of most technologies used by the project, and a smooth falloff. Deviation from one of those three aspects would probably lead to sub-optimal productivity.

But what about “T-shaped” people model? It was misunderstood. Valve is not just another software company, and their models don't necessarily apply in other companies. Valve's handbook is very clear about the intentions of their model:

We value “T-shaped” people, that is, people who are both generalists (highly skilled at a broad set of valuable things—the top of the T) and also experts (among the best in their field within a narrow discipline—the vertical leg of the T).

This recipe is important for success at Valve. We often have to pass on people who are very strong generalists without expertise, or vice versa. An expert who is too narrow has difficulty collaborating. A generalist who doesn't go deep enough in a single area ends up on the margins, not really contributing as an individual.

Two things should be highlighted here:

At Valve, it is not a question of being a good Java developer. It's a question of being “among the best in their field,” which is not the case of 99% of software developers (and I'm ways too kind here).

The generalist aspect Valve wants from their employees is not needed to force people to work with stuff they don't master. The goal is to ensure that people don't have difficulty collaborating. Without basic understanding of other domains, collaboration with people working in those other domains will necessarily have a negative impact.

This has nothing to do with the goals of other companies, who need specialized persons who are also able to handle themselves tasks from other domains. For Valve, “T-shaped” people is the appropriate model; for other companies, it is only misleading, and should be replaced by the falloff model I presented here.