Visual management

I discovered Visual management blog in 2013. Although I already heard about Kent Beck's Big Visible Chart, I've never actually seen visual management in practice before. For me, tickets went straight to FogBugz or TFS and remained there, immaterial and elusive.

The idea of moving the tickets from the cold nowhere of virtuality to the real world of objects was appealing, so I jumped on the occasion when starting the Next Great Thing—my one-man Continuous Integration environment project.

My usage was slightly different from the one described in Visual management blog. I'll explain how and why I made some changes, and what do I think about the idea of moving from FogBugz/TFS to a real-world board.

“I'm different”

At first, I wanted to stick to the precise way described in Visual management blog. “Don't reinvent the wheel”—I was telling myself: other people spent a lot of time thinking about this stuff and explaining it. But at the same time, I understood that my situation was different from their.

The first difference is that I'm working alone. Visual management is a way to represent N-dimensional data using position, colors and shapes, and the major problem is that there are too many dimensions:

- This task is in progress, and that one is finished.

- That task is assigned to Jeff, while this one should be handled by Cindy.

- Those two tasks are extremely important, because they can be blocking in a near future.

- This task is related to interaction design and has nothing to do with programming.

- etc.

In my case, I was lucky: being the only member of the team, I had one dimension less: all tasks were necessarily assigned to me. On the other hand, I could be working on several projects at the same time, and using multiple boards was not an option.

I finally decided to handle three dimensions:

The type of task. Types are mutually exclusive: while it's sometimes not obvious to pick a type for a task, it's not that important, after all.

- Development: this encompasses architecture, design, testing and implementation, i.e. anything within a scope of whiteboard and IDE.

- Design: this deals with tasks related to interaction design, graphics, communication, etc.

- Infrastructure: here, the focus is on the environment. If I have to deploy a VM, create a backup, configure an application, etc., this is it.

- Non-programming related tasks (often administrative stuff). Hardware-related issues (like a failed HDD) are here too.

- Pre-production, production and post-production: deals with my movie-related projects as well as still photography.

The status. Here, Visual management blog uses an approach that I personally find not particularly straightforward. It slices the status into two: first, the task can be not started, in progress or finished; second, the task can be “please test”, “bug”, etc. Since I don't see the benefit of such separation, I used the same approach for all statuses, which are non-mutually exclusive.

Done: the task is finished. It's kept here until the retrospective, but it is actually finished, which also means tested. This is also why I don't understand the “please test” tag in Visual management blog: if the task is untested, it's not done. If the task is not done, why would someone flag it “please test”, and not other tasks which are not done yet?

Current: that is, I'm working on this task. In an ideal world and if I were a robot, I would have only one task labelled as current and not-yet-done. Since I'm not a robot but an unorganized human being who switches from task to task all the time, there are usually one to four current tasks. Four is really bad; I admit it and do my best to improve myself.

Critical: this is for the tasks which are blocking and/or should be done ASAP. If I notice that automated backups of SVN repositories are down, this is damn critical.

WTF: this tag indicates that something got completely wrong with the task. Either I failed on management level (like I'm on this simple 30-minutes task for the last five days) or technically (like the thing is completely out of control and I have no idea how to do the task). It's like a cry for help, but to myself.

The project, since I work on multiple projects at a time, and I only have space for one board. The attribution is mutually-exclusive.

The iteration switch.

Some tasks are expected to be done during the current iteration.

Other tasks will wait in a sort of backlog.

This means that I have to represent four dimensions: two with mutually-exclusive values, one with non-mutually-exclusive values and one with a mutually-exclusive boolean. That should be easy.

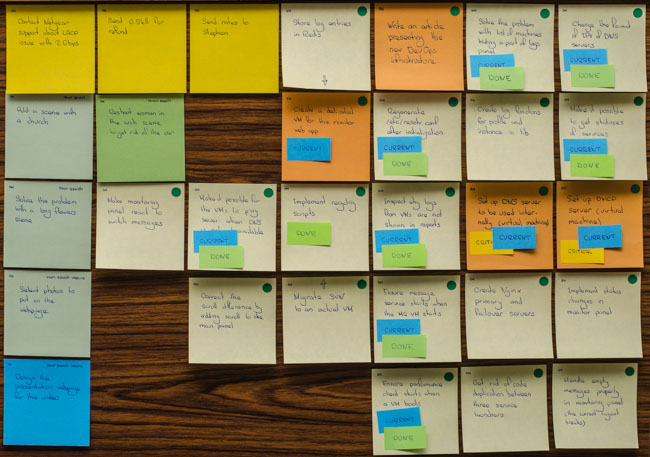

First, I decided to use colors of post-its to show their type. Development-related post-its are light yellow. Design ones are blue. Infrastructure ones are orange. Non-programming ones are yellow. Different types of green are used for pre-production, production and post-production.

Then, logically, small post-its decorate large ones in order to tag them. Tagging is actually the only way to represent non-mutually exclusive criteria here, and small tags seem to be a good visual representation of tags. Different colors represent different statuses, given that the status is also indicated in all letters to ensure redundancy with the colors. Actually, “critical” and “WTF” share the same color, since they share the same nature.

Projects are marked with small dots in the top right corner. Minor projects don't have a dot, but a hand-written name.

Finally, for the iteration switch, I used the position of the post-its. On the right side of the board (where I can see the tasks without moving my chair) there are tasks to do during the current iteration. On the left side, there is a backlog.

The full view of the right side of the board containing tasks to do during the current iteration. Similar tasks, not shown here, are on the left side, waiting for future iterations.

Mistakes I've done

One of my mistakes was the intention to handle dependencies—an old habit from bug tracking systems. Task boards are a weak representation of dependencies, and I'm pretty sure that having tasks which depend on other tasks is not very agile.

As a result, managing dependencies was a nightmare. I couldn't move a post-it without moving the dependants and the dependees, which resulted in a very rigid board. Moreover, that's not that important, after all. Dependencies are essential when tasks are assigned to team members, therefore PERT is essential in Waterfall. On the other hand, in Agile, members of a small team know exactly what's happening with the project and commit to the tasks they enjoy, which also means that they grasp the possible dependencies with ease.

Another mistake was to use one board for all projects. While it somehow works in my particular case, even in my case, I clearly see the difficulty it presents to not being able to identify with ease the tasks for a single project.

Although I'll probably continue to use one board for everything, I would imagine that this would be a mistake to do the same in a team.

Conclusions

I've now used task boards for more than six months. In the past, I've used:

- FogBugz: my preferred bug tracking system,

- TFS: good enough but more unfriendly,

- Jira: I haven't used it too much but have in impression that it is very capable and well-done system,

- Redmine: the PhpBB of bug tracking systems, made with no user experience in mind,

- Two in-house bug tracking systems.

Therefore, I imagine that I'm in a position to compare bug tracking systems to the visual management approach.

The first thing is that a task board doesn't replace a fully-featured bug tracking system, and I imagine that it was never designed to do it. Those are just different tools for different needs.

A bug tracking system tracks bugs over time. It doesn't do a great job of showing the status of the project right now, but it does an excellent job (when done correctly) when it comes to remembering that this precise bug was already filed on February 14th, closed the next day by Mike, then confirmed as solved by testing team, and then reopened, two months later when we had our new junior programmer gone mad and creating dozens of regressions all over the code base. Post-its are volatile, and make such traceability impossible. Someone may remember that there was a related task approximately three weeks ago (or was it two?), but then, good luck for getting the details.

Task boards, on the other hand, pursues the goal of showing in a clear way the status of the project—right now, obviously, but also for the next weeks. They can't show precisely what the team will be doing in a week or two, but it doesn't matter. The only thing that matters is that everyone knows what is the next task to do, as well as the overall direction. This is exactly what I've explained in Roadmaps, goals, morale, beliefs and motivation article, and I believe that visual management approach makes an excellent job of showing exactly everything that is needed to be shown, and only that. Bug tracking systems do not, and may sometimes have a negative effect on the morale of the team.

In my opinion, a task board is a great tool in Agile environment. For a small team, it gives an opportunity to be up to date on what's going on and to keep motivation high through proper information cast. Since knowing what to do and remain motivated is two top priority things in project management, I think that not using a task board is a big mistake.

However, the tool has its limitations that are worth taking in consideration when choosing to use visual management:

It applies only to a team where all members work in the same part of the building. You have four developers in Oregon and two others in Tel Aviv? Don't use a task board, it's not for you. You have four developers at the second floor of your building, and three others at the fifth floor? The task board is not for you.

The condition sine qua non for using the task board is to make it possible for any member of the team to reach the board within thirty seconds in order to add a post-it, add a tag to a post-it, move a post-it or simply read one. Not giving this opportunity to at least one member will result in a constantly obsolete board which is not used by everyone. You definitely don't want that.

It requires effort from every team member to maintain the board. I had to work with people who are reluctant to open a bug tracking system even after they receive an e-mail telling that there is a ticket assigned to them, or people who are just don't want to write a ticket correctly. There is no hope that they will enjoy using a task board.

An important part of the board is the overall organization—an aspect which is highlighted a lot in Visual management blog. If you can't make your team organized, the board will suffer.

More importantly, the board requires constant effort: an obsolete board is useless, probably even harmful.

It is based on hand writing. It may be strange that I mention this, but this aspect is critical. If one or several of team members are unable to write correctly and intelligibly, either they won't use the board (which leads to the same problems as with a remote team discussed above).

To conclude, if you work with/in a collocated team of highly motivated and committed individuals, visual management's task board is an excellent tool which can greatly improve the morale and the performance of the team while freeing the team from a burden of working with a bug tracking system. But beware of cases where this tool wouldn't be ideal and could make more harm than good.

Also, remember that a task board is not a substitute for a bug tracking system. Although it may be for the team members, sometimes project manager (or another specific person) will have to ensure the link between the task board used by the team and the bug tracking system used by the customer.